When you talk about the sound that defined a generation of British music, you have to talk about John Squire. As the quiet, artistic engine behind The Stone Roses, Squire did for ’80s and ’90s indie what Hendrix did for ’60s blues-rock: he grabbed it, turned it upside down, and painted it in psychedelic colours. Part chiming Rickenbacker jangle, part blistering blues-rock, his style is a masterclass in texture, melody, and attitude.

Squire wasn’t just a guitarist; he was (and is) a visual artist, and he approached the fretboard like a canvas. He didn’t just play chords and solos; he created soundscapes. His playing is defined by a brilliant fusion of ’60s jangle (think The Byrds) and ’70s firepower (think Page and Hendrix), all filtered through a haze of perfectly chosen effects. He made the guitar sound liquid, reverse, and anthemic, often all in the same song.

Getting the Squire Sound: It’s All in the Sauce

Before you can play the riffs, you need to understand the tone. While Squire famously used Rickenbackers, Strats, Teles, and Les Pauls (especially a ’59 Standard) throughout his career, his “classic” sound is less about one guitar and more about the effects.

To get in the ballpark, your pedalboard essentials are:

Chorus: This is arguably the most crucial effect for the early material. A lush, shimmering chorus (like a Boss CE-2) is what gives “Waterfall” its watery, liquid texture.

Delay: Squire often used delay not just for echo, but for rhythmic texture, sometimes dialing in reverse delays to create that signature psychedelic, “backward” sound.

Wah-Wah: On tracks like “I Am the Resurrection,” the wah isn’t just for ’70s funk solos. He’d often “park” the pedal in one position (a “cocked wah”) to use it as a powerful, nasal-sounding filter, cutting through the mix.

Overdrive/Fuzz: From a subtle bluesy breakup (like an Ibanez Tube Screamer) to full-on saturated fuzz for his heavier blues-rock moments, his gain was always expressive and dynamic.

He typically ran these into classic amps like Fender Twin Reverbs (for crystalline cleans) or Marshall stacks (for rock ‘n’ roll crunch).

3 Essential Tracks: Your John Squire Starter Pack

Ready to plug in? Here are three quintessential Squire tracks and how to approach capturing their magic.

1. “Waterfall”

This is the quintessential Stone Roses jangle-pop anthem. The guitar part is a shimmering, arpeggiated masterpiece.

The Approach: This song is all about texture and articulation. Use your bridge pickup (on a Tele, Strat, or Rickenbacker) and drench it in a slow, deep chorus effect. Add a touch of delay to help the notes bloom. The main riff isn’t strummed; it’s a delicate, arpeggiated part based around D, G, and A major shapes. Focus on letting the notes of each chord ring into one another to create that beautiful, overlapping cascade of sound.

2. “I Am the Resurrection”

This is a song of two distinct halves: the upbeat, melodic main song and the iconic, seven-minute funk-rock jam that closes the album. We’re focusing on that legendary outro.

The Approach: This is your license to be a psychedelic blues god. The entire jam is rooted in the E minor pentatonic or E blues scale. Kick on your wah pedal and a solid overdrive or fuzz. The key here is how Squire uses the wah: he rakes the strings, uses it as a rhythmic filter, and parks it in different spots to get those sharp, funky tones. It’s pure improvisation. Don’t just play licks; explore the sounds, experiment with feedback, and build the tension just like he does.

3. “Love Spreads”

From the band’s grittier Second Coming album, this track is a different beast entirely. It’s a heavy, swaggering, blues-rock monster.

The Approach: Forget standard tuning. This song is played in Open G tuning ($D-G-D-G-B-D$). This is the secret to its massive, bluesy sound. You’ll also need a guitar slide. The main riff is a heavy, slide-based lick played on the lower strings. You’ll want a thick, overdriven tone for this one—think Les Paul into a cranked Marshall. This song is all about attitude, heavy-handed picking, and mastering that vocal-like slide vibrato. It’s Squire channeling his inner Jimmy Page and delta blues heroes.

The Legacy: The Guitarist’s Guitarist

John Squire’s influence is immeasurable. He was the poster boy for the generation of guitarists (hello, Noel Gallagher) who proved you could be an indie kid and a guitar hero at the same time. He brought melodic artistry and sheer technical firepower back to alternative music, inspiring countless players to look beyond simple power chords and explore the sonic possibilities of a guitar and a few pedals.

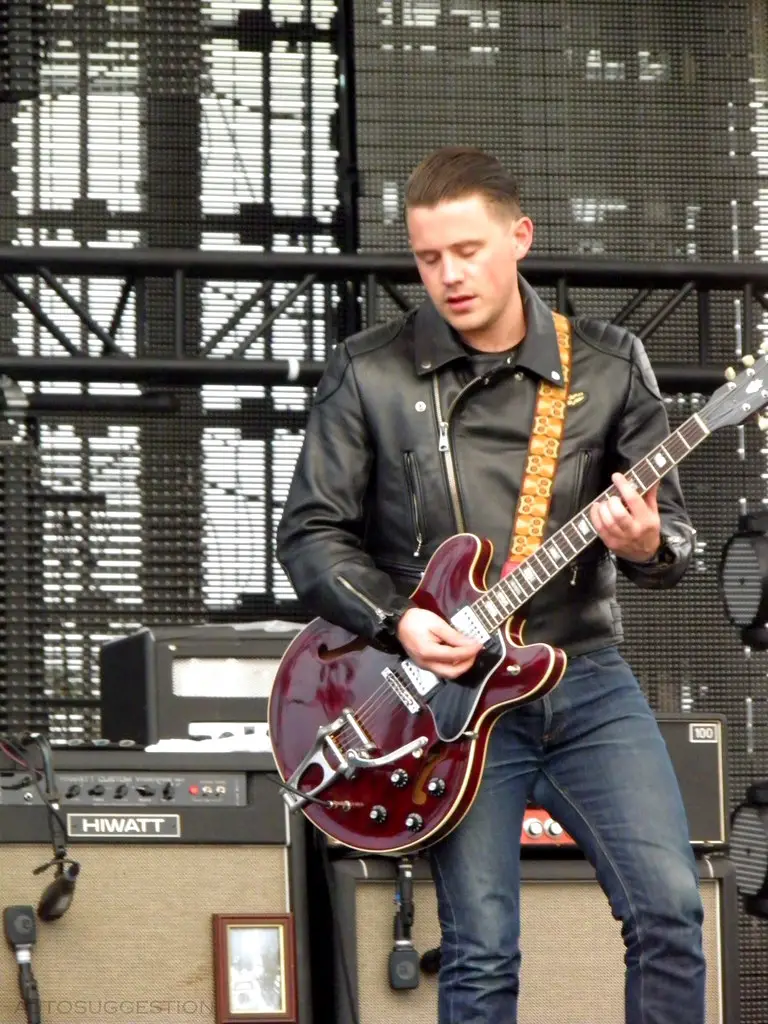

Cover photo credit “John Squire” by Silly Little Man is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0